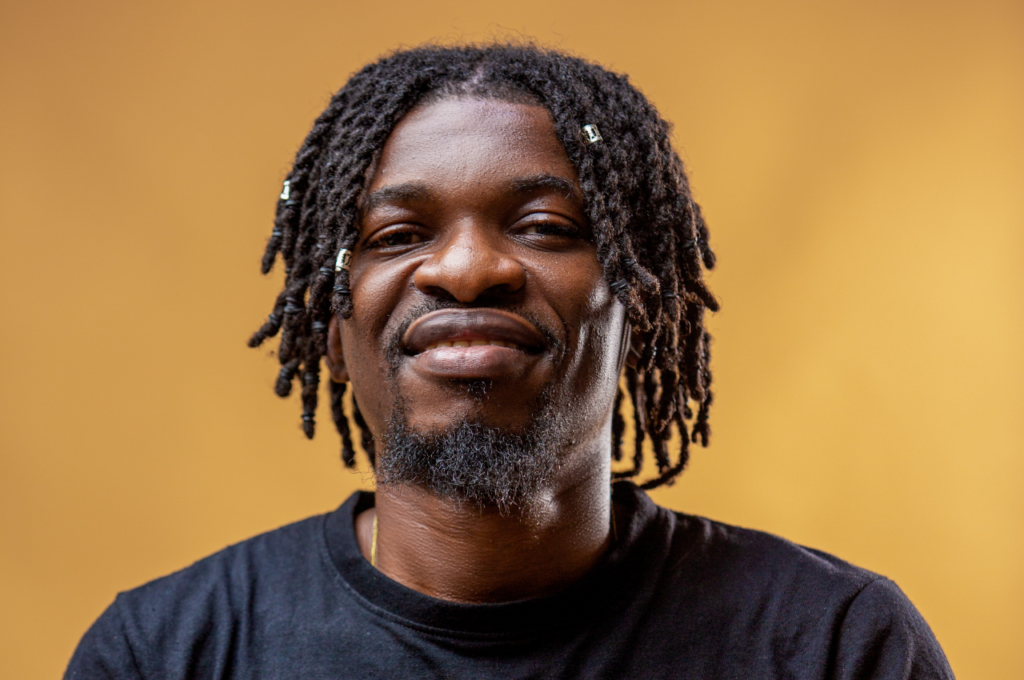

How Oluwatobi Fagbohungbe Is Professionalising Quality Engineering in Nigeria’s Tech Sector

As Nigerian technology companies scale across millions of users and multiple markets, one constraint has become harder to ignore: products that grow faster than the systems meant to keep them reliable. Failures that once passed as technical hiccups are now reputational risks, regulatory issues and balance‑sheet problems. That pressure point is where Oluwatobi Fagbohungbe has built his career. For nearly a decade, while much of the conversation around African tech talent centred on software developers, Fagbohungbe focused on a less visible but increasingly critical discipline: quality engineering and software testing. Through initiatives including Qace Academy and TestForge, he has helped shape a pipeline of professionals trained not just to build software, but to ensure it works at scale. Building From a Skills Gap Fagbohungbe’s work did not begin with venture capital or institutional support. In 2017, as Nigeria’s startup ecosystem expanded rapidly, he observed a recurring disconnect. Training programmes were producing learners, but companies were still struggling to hire job‑ready quality engineers. Rather than launching a platform, he started teaching. He worked informally with peers and early‑career professionals, emphasising practical testing skills, workplace expectations and exposure to real projects. Over time, that informal effort evolved into a structured community. Today, graduates from his programmes are employed across Nigeria’s fintech and consumer‑technology sector, including at Andela, Moniepoint, Interswitch, Flutterwave, OPay and MTN. The metric that matters is placement, not participation. Training for Deployment, Not Certification Qace Academy was not designed as a conventional bootcamp. Its focus has been on addressing a persistent weakness in African tech education: the transition from training to employment. Instead of framing testing as a checklist‑driven function, the curriculum emphasises systems thinking, business risk and user impact. Trainees are taught how products fail, why failures matter commercially and how quality affects trust as platforms scale. That approach reflects a broader shift within African technology companies. As products expand across borders and regulatory environments, quality failures increasingly translate into compliance exposure and financial loss. By combining mentorship, portfolio development and interview readiness, Qace Academy positioned itself less as a training provider and more as a talent pipeline aligned with employer expectations. Mentorship as Market Alignment The same thinking underpins the QaTechBro Mentorship Program, now in its fourth year. Early‑career professionals are paired with active practitioners, including mentors working outside Nigeria. The objective is calibration rather than motivation. Participants gain insight into global standards, hiring benchmarks and the realities of distributed work. The programme functions as a bridge between local training and international market expectations. TestForge emerged as a complementary layer. Rather than operating as a traditional conference, it serves as an access mechanism. Scholarships and funded placements into Qace Academy programmes link community engagement directly to opportunity. As automation and artificial intelligence gain traction, TestForge has also become a forum for reframing the role of quality engineers. Fagbohungbe presents AI not as a threat, but as a pressure point that raises the bar for judgement, system awareness and ethical responsibility. A System, Not a Series of Projects What distinguishes Fagbohungbe’s work is not any single initiative, but how they connect. From early exposure to structured learning, mentorship and professional integration, the programmes operate as parts of one system. Even Qace Academy Kids reflects this long‑term view, introducing logic and quality fundamentals early rather than attempting to retrofit skills later. The model offers a broader signal for Africa’s technology ecosystem. Sustainable talent development may depend less on chasing new tools and more on building pathways that reflect how careers actually form. Why It Matters As African fintech and consumer platforms mature, quality engineering is moving from the background to the centre of product strategy. Reliability, compliance and user trust are no longer optional features. Fagbohungbe’s contribution sits squarely at that intersection. It is not promotional or headline‑driven, but structural. His work suggests that the next phase of Africa’s technology growth will be shaped as much by depth as by scale. And that the builders strengthening foundations may ultimately have as much influence as those building the most visible products. In that sense, Oluwatobi Fagbohungbe is not just running programmes. He is helping redefine what readiness looks like in Nigeria’s technology sector, one quality engineer at a time.